The idea of plugins and the SimulatorAccess and Introspection classes#

The most common modification you will probably want to do to ASPECT are to switch to a different material model (i.e., have different values of functional dependencies for the coefficients \(\eta,\rho,C_p, \ldots\) discussed in Coefficients); change the geometry; change the direction and magnitude of the gravity vector \(\mathbf g\); or change the initial and boundary conditions.

To make this as simple as possible, all of these parts of the program (and some more) have been separated into what we call plugins in which, for example, each one of many material models is implemented as a separate class in the “material model plugin system”; each one of many geometries is implemented as a separate class in the “geometry model plugin systems”; etc. In the input file, you can then select one (or for some plugin systems, multiple) plugins from a plugin system to pick which material model, geometry model, etc., it is you want in your simulation.

In ASPECT, nearly everything is implemented as plugins. There are a lot of plugins already, see Fig. 293. At the same time, there are situations where you want to do something that is not yet available in the existing plugins. Say, you want a very specific geometry; or, a common situation, you want to implement a specific postprocessor that is not yet implemented – perhaps you are interested in evaluating only the vertical component of the velocity in a particular part of the domain. In these cases, the plugin system allows you to quickly add an implementation of the necessary plugin which will then be available in the input file like all of the existing plugins of that particular system. In writing a new plugin, you will often find it useful to look at the existing plugins as starting points for the implementation of your own plugin.

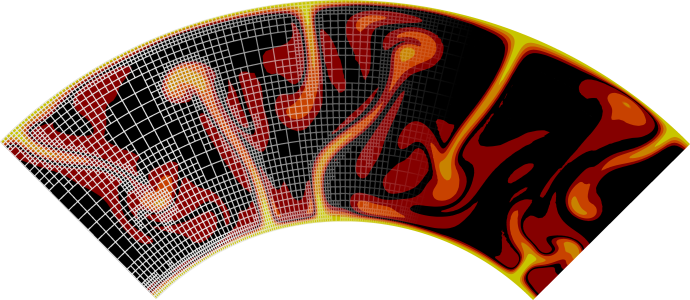

Fig. 293 The graph of all current plugins of ASPECT. The yellow octagon and square represent the Simulator and SimulatorAccess classes. The green boxes are interface classes for everything that can be changed by plugins. Blue circles correspond to plugins that implement particular behavior. The graph is of course too large to allow reading individual plugin names (unless you zoom far into the page), but is intended to illustrate the architecture of ASPECT.#

The central idea of plugins is achieved is through the following two steps:

The core of ASPECT really only communicates with material models, geometry descriptions, etc., through a simple and very basic interface. These interfaces are declared in the include/aspect/material_model/interface.h, include/aspect/geometry_model/interface.h etc., header files. These classes are always called

Interface, are located in namespaces that identify their purpose, are derived from the common base classPlugins::InterfaceBase, and their documentation can be found from the general class overview in https://aspect.geodynamics.org/doc/doxygen/classes.html.To show an example of a rather minimal case, here is the declaration of the aspect::GravityModel::Interface class (documentation comments have been removed):

template <int dim> class Interface : public Plugins::InterfaceBase { public: virtual Tensor<1,dim> gravity_vector (const Point<dim> &position) const = 0; };

If you want to implement a new model for gravity, in its simplest form you just need to write a class that derives from this base class and implements the

gravity_vectorfunction. If your model wants to read parameters from the input file, you also need to have functions calleddeclare_parameters()andparse_parameters()in your class with the same signatures as the ones declared in thePlugins::InterfaceBasebase class. On the other hand, if the new model does not need any run-time parameters, you do not need to overload these functions.[1]Each of the other plugin categories (mentioned above or otherwise) have several implementations of their respective interfaces that you can use to get an idea of how to implement a new model.

At the end of the file where you implement your new model, you need to have a call to the macro

ASPECT_REGISTER_GRAVITY_MODEL(or the equivalent for the other kinds of plugins). For example, let us say that you had implemented a gravity model that takes actual gravimetric readings from the GRACE satellites into account, and had put everything that is necessary into a classaspect::GravityModel::GRACE. Then you need a statement like this at the bottom of the file:ASPECT_REGISTER_GRAVITY_MODEL (GRACE, "grace", "A gravity model derived from GRACE " "data. Run-time parameters are read from the parameter " "file in subsection 'Radial constant'.");

Here, the first argument to the macro is the name of the class. The second is the name by which this model can be selected in the parameter file. And the third one is a documentation string that describes the purpose of the class (see, for example, Gravity model for an example of how existing models describe themselves).

This little piece of code ensures several things: (i) That the parameters this class declares are known when reading the parameter file. (ii) That you can select this model (by the name “grace”) via the run-time parameter

Gravity model/Model name. (iii) That ASPECT can create an object of this kind when selected in the parameter file.Note that you need not announce the existence of this class in any other part of the code: Everything should just work automatically.[2] This has the advantage that things are neatly separated: You do not need to understand the core of ASPECT to be able to add a new gravity model that can then be selected in an input file. In fact, this is true for all of the plugins we have: by and large, they just receive some data from the simulator and do something with it (e.g., postprocessors), or they just provide information (e.g., initial meshes, gravity models), but their writing does not require that you have a fundamental understanding of what the core of the program does.

The procedure for the other areas where plugins are supported works essentially the same, with the obvious change in namespace for the interface class and macro name.

In the following, we will discuss some general requirements for individual plugins. In particular, let us discuss ways in which plugins can query other information, such as the current state of the simulation. To this end, let us not consider those plugins that by and large just provide information without any context of the simulation, such as gravity models, prescribed boundary velocities, or initial temperatures. Rather, let us consider as an example postprocessors that can compute things like boundary heat fluxes (see Postprocessors: Evaluating the solution after each time step).

Recall that the base class for postprocessors looks as follows:

template <int dim>

class Interface : public Plugins::InterfaceBase

{

public:

virtual

std::pair<std::string,std::string>

execute (TableHandler &statistics) = 0;

virtual

std::list<std::string>

required_other_postprocessors () const;

virtual

void save (std::map<std::string, std::string> &status_strings) const;

virtual

void load (const std::map<std::string, std::string> &status_strings);

};

The required_other_postprocessors(), save(), and load()functions are discussed in the documentation of that class, and we will ignore it here. Rather, we want to discuss how to implement a simple postprocessor class that does not need the facilities of these other three functions, and only overloads theexecute()` function. We start with the following

class declaration for our own postprocessor class:

template <int dim>

class MyPostprocessor : public aspect::Postprocess::Interface

{

public:

std::pair<std::string,std::string>

execute (TableHandler &statistics) override;

// ... more things ...

The idea is that in the implementation of the execute function you would

compute whatever you are interested in (e.g., heat fluxes) and return this

information in the statistics object that then gets written to a file (see

Overview and Visualizing statistical data). A

postprocessor may also generate other files if it so likes – e.g.,

graphical output, a file that stores the locations of particles, etc. To do

so, obviously you need access to the current solution. This is stored in a

vector somewhere in the core of ASPECT.

However, this vector is, by itself, not sufficient: you also need to know the

finite element space it is associated with, and for that the triangulation it

is defined on. Furthermore, you may need to know what the current simulation

time is. A variety of other pieces of information enters computations in these

kinds of plugins.

All of this information is of course part of the core of ASPECT, as part of the aspect::Simulator class. However, this is a rather heavy class: it’s got dozens of member variables and functions, and it is the one that does all of the numerical heavy lifting. Furthermore, to access data in this class would require that you need to learn about the internals, the data structures, and the design of this class. It would be poor design if plugins had to access information from this core class directly. Rather, the way this works is that those plugin classes that wish to access information about the state of the simulation inherit from the aspect::SimulatorAccess class. This class has an interface that looks like this:

template <int dim>

class SimulatorAccess

{

protected:

double

get_time () const;

std::string

get_output_directory () const;

const LinearAlgebra::BlockVector &

get_solution () const;

const DoFHandler<dim> &

get_dof_handler () const;

// ... many more things ...

This way, SimulatorAccess makes information available to plugins without the need for them to understand details of the core of ASPECT. Rather, if the core changes, the SimulatorAccess class can still provide exactly the same interface. Thus, it insulates plugins from having to know the core. Equally importantly, since SimulatorAccess only offers its information in a read-only way it insulates the core from plugins since they can not interfere in the workings of the core except through the interface they themselves provide to the core.

Using this class, if a plugin class MyPostprocess is then not only derived

from the corresponding Interface class but also from the

SimulatorAccess class (as indeed most plugins

are, see the dashed arrows in Fig. 293), then you can write a member

function of the following kind (a nonsensical but instructive example; see

Postprocessors: Evaluating the solution after each time step for more details on what postprocessors do and how they are implemented):[3]

template <int dim>

std::pair<std::string,std::string>

MyPostprocessor<dim>::execute (TableHandler &statistics)

{

// compute the mean value of vector component 'dim' of the solution

// (which here is the pressure block) using a deal.II function:

const double

average_pressure = VectorTools::compute_mean_value (this->get_mapping(),

this->get_dof_handler(),

QGauss<dim>(2),

this->get_solution(),

dim);

statistics.add_value ("Average pressure", average_pressure);

// return that there is nothing to print to screen (a useful

// plugin would produce something more elaborate here):

return std::pair<std::string,std::string>();

}

The second piece of information that plugins can use is called

“introspection”. In the code snippet above, we had to use that the

pressure variable is at position dim. This kind of implicit knowledge is

usually bad style: it is error prone because one can easily forget where each

component is located; and it is an obstacle to the extensibility of a code if

this kind of knowledge is scattered all across the code base.

Introspection is a way out of this dilemma. Using the

SimulatorAccess::introspection() function returns a reference to an object

(of type aspect::Introspection)

that plugins can use to learn about these

sort of conventions. For example,

this->introspection().component_mask.pressure returns a component mask (a

deal.II concept that describes a list of booleans for each component in a

finite element that are true if a component is part of a variable we would

like to select and false otherwise) that describes which component of the

finite element corresponds to the pressure. The variable, dim, we need above

to indicate that we want the pressure component can be accessed as

this->introspection().component_indices.pressure. While this is certainly

not shorter than just writing dim, it may in fact be easier to remember. It

is most definitely less prone to errors and makes it simpler to extend the

code in the future because we don’t litter the sources with “magic

constants” like the one above.

This aspect::Introspection class has a significant number of variables that can be used in this way, i.e., they provide symbolic names for things one frequently has to do and that would otherwise require implicit knowledge of things such as the order of variables, etc.